Chromatic Coppersmith Theory

Today, I want to discuss the opposite procedures of deformations and contractions of complex-orientable cohomology theories.

Really, all I want is to illustrate the fact that, with the appropriate combinations of both procedures, we obtain new cohomology theories. So, we’re going to examine the construction of one-parameter families of cohomology theories via one-parameter deformations of formal group laws — of particular interest is the case where a continuous deformation causes an increase of chromatic height.

Motivation and Story Leading To This Construction

I was playing with the concept of group contraction, and thinking about the construction of elliptic cohomology theories.

I accidentally constructed a model of Morava E-theory of height 2 at the prime 3. (We didn’t realize that it was \(E_{(2)}(3)\) at first, we just thought it was some weird cohomology theory.)

I found this kind of enlightening and so I want to show you how I came across it.

Morava constructed a family of elliptic cohomology theories by deforming K-theory (well, by deforming the multiplicative group associated to K-theory). His construction can be viewed as a recipe:

- start with a point of interest (an algebraic group) e.g., \(\mathbb{C}^\times\) e.g., \(y^3 = x^3 - x \) over \(\mathbb{F}_3\)

- deform that point (create a family of algebraic groups indexed by one parameter) e.g., \(\mathbb{C}^\times/q^{\mathbb{Z}}\) where \(q:= e^{2\pi i}\), we vary the norm of \(0 \leq |q| < 1\). e.g., \(y^3 = x^3 + tx^2 - x\) over \(\mathbb{F}_3[[t]]\)

- look at the formal group laws associated to your family, this is still indexed by one parameter (in fact, they can be viewed as ONE formal group law, if you keep the parameter formal)

- either apply the Landweber exact functor theorem to the whole family stalkwise (specializing the parameter), or apply the Landweber exact functor theorem to the ONE formal group law (keeping the parameter formal).

Let me say this again, because when I explain this to people they like me to say it twice.

Morava’s deformation method is a recipe which consists of 4 steps:

- construct a continuous family of smooth algebraic groups indexed by q

- construct a continuous family of formal group laws indexed by q

- construct a family indexed (indexed by q) of contra-functors from Top to AbGrp (“potential” cohomology theories — we don’t know if they are exact yet)

- prove that each member of this family of contravariant functors is exact (or treat the family as one functor, keeping the variable formal, and prove that this functor is exact)

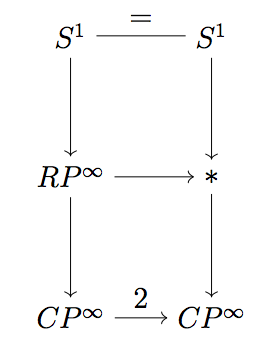

Derivation of the formal group law \(F_t\) and its 3 series

We take an easy example of an elliptic curve group contraction, and set it into an algebraic family, and look at how the formal group varies in the family. (This was explicitly explained to me by Dr. Lubin, thank you!) \(E = E_t : y^2 = x^3 + tx^2 - x\)

The elliptic curve is defined over \(R = \mathbb{Z}[t]\), but it is not elliptic everywhere, in the sense that there are prime ideals p of Spec (R) for which E is not elliptic over \(R/p\). The discriminant of \(E_t\) is \(\Delta = 16(4-t^2)\), so we have bad reduction over the prime \(2\). To be elliptic everywhere, we invert 2 and live in the coefficient ring \(\mathbb{Z}[1/2][[t]]\).

The easiest way to get the formal group is to take the logarithm \(L(x)\) first, then find the formal group \(F\) satisfying the relation \(L(F(x,y)) = L(x) + L(y)\). We do this for our family of curves (by homogenizing, solving for \(z\), and solving for the invariant differential, \(\omega\)), and find:

\begin{align} L(x) & \equiv x + t\frac{x^3}{3} \ &+ (-2 + t)\frac{x^5}{5} \ &+ (-6t + t^3)\frac{x^7}{7} \ & + (2 - 4t^2 + \frac{1}{3}t^4)\frac{x^9}{3} \ &+ (30t - 20t^3 + t^5)\frac{x^{11}}{11} \ & + (-20 + 90t^2 - 30t^4 + t^6)\frac{x^{13}}{13} \mod (x^{14}) \end{align}

Before we go on to get the formal group, notice what happens when \(3 \mid t\): then the logarithm is just \(x-2x^5/5 + 2x^9/3 - 20x^{13}/13 + …\). We get \(x^p/p\) terms at the prime for which \(y^2 = x^3 - x\) is ordinary, and no term of degree p at the primes at which the curve \(E_t\) is supersingular, but there will be a term \(x^{p^2}/p\), as we see in degree 9. Let us now see the formal group, \(L^{-1}(L(x) + L(y))\): \begin{align} F_t & \equiv x + y \ & - t(x^2 + xy^2) \ & + 2(x^4y + xy^4) + (4+t^2)(x^3y^2 + x^2y^3) \ & + 2t(x^6y+xy^6) - (4t+t^3)(x^4y^3+ x^3y^4) \ & + (-2 + 2t^2)(x^8y + xy^8) + (8+2t^2)(x^6y^3+x^3y^6) \ & + (16 + 8t^2 + t^4)(x^5y^4 + y^4x^5) \mod (x,y)^{11} \end{align}

This is an expansion of the first few terms of our formal group over the polynomial ring \(\mathbb{Z}[t]\). Thus we can consider it an algebraic family of formal groups, or an analytic such. Or we can reduce it \(\mathbb{F}_p[t]\).

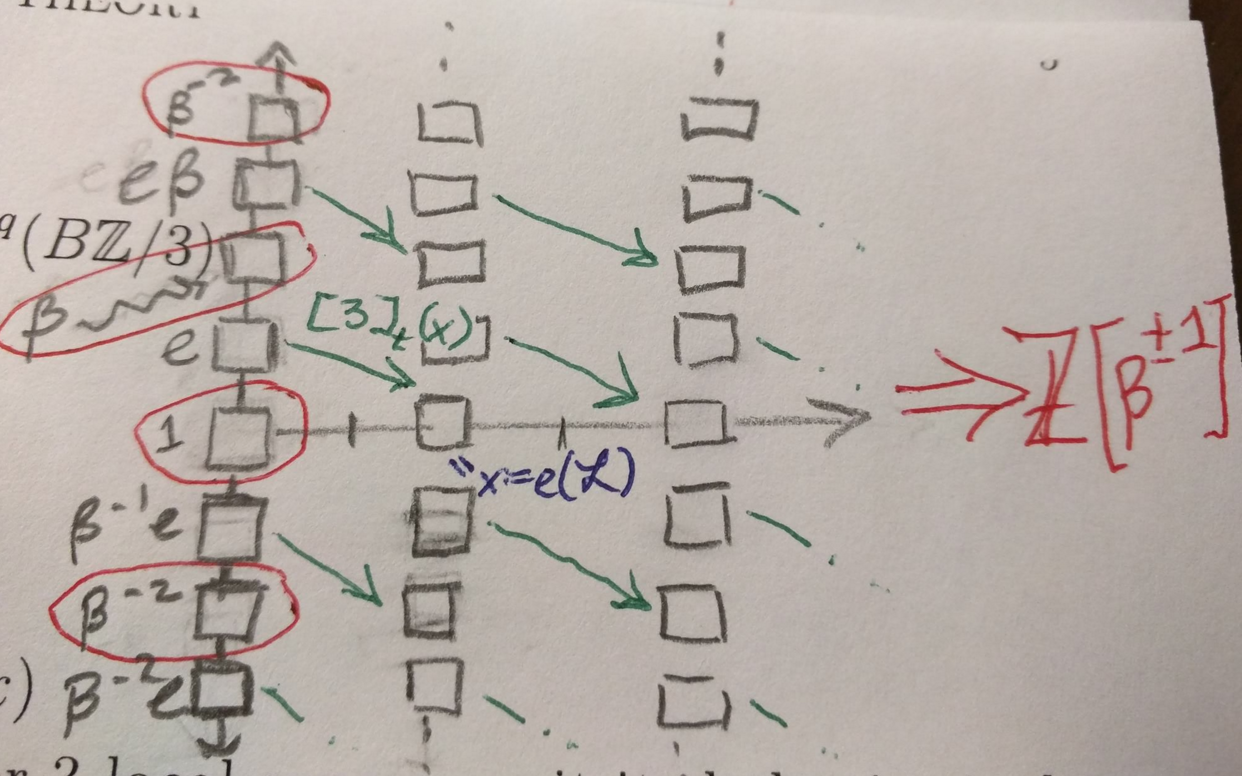

| Doing this for p = 3, we see that if \(3 \nmid t\), we get a formal group of height one, while if \(3 | t\), the height is two, since the first 3-power terms are in degree 9. It may be clearer to write out the series: |

\begin{align} [3]_t(x) \equiv 3x - 8tx^3 + (96 + 24t^2)x^5 + (-288t-72t^3)x^7 \ + (2432 + 1472t^2 + 216t^4)x^9 \mod (x^{11}) \end{align}

What’s the moral of the story? Here, we started with an elliptic curve over (a localization of) \(\mathbb{Z}[t]\) and got a formal group over \(\mathbb{Z}[t]\), which we might reduce modulo any odd prime \(p\) to get, at that prime, a family of formal groups, not even an analytic one, but algebraic, since the coefficients were always polynomials in \(t\).

Construction of \(\mathbb{L}^t_*(-)\)

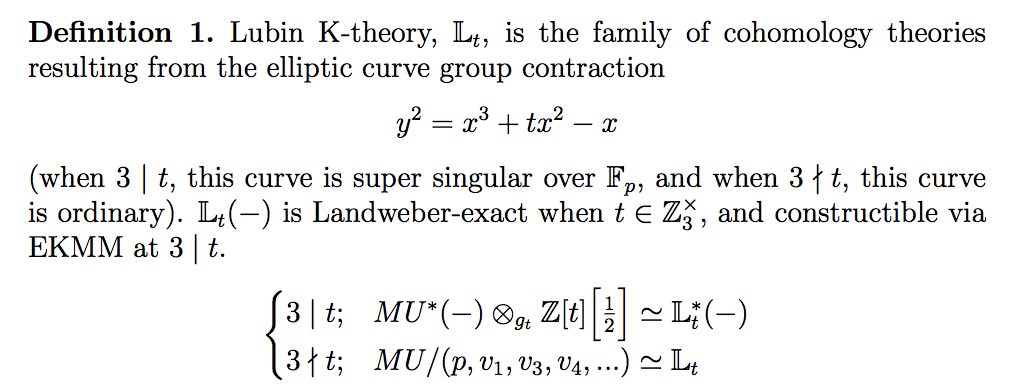

Given a formal group \(F_t\), we may construct Lubin K-theory using Landweber-Ravenel-Stong. Let me make this clear, we are treating the formal group law family as one formal group law, otherwise, when \(3 \mid t\), our formal group law is not Landweber exact.

\(MU^*(-) \otimes_{MU^*} \mathbb{Z}[t][\frac{1}{2}]\simeq \mathbb{L}_t^*(-)\)

Note that the \(MU^*\)-module structure induced by the genus \(g_t: MU^* \to \mathbb{Z}[t]\) associated to the formal group law \(F_t(x,y)\).

Proof of Exactness

| The exactness of each member of our family of cohomology theories \({\mathbb{L}_t | \forall t \in R}\) is shown, we examine the family in two cases. Though, really, we are treating the family as one formal group law which is exact (due to the first case) |

As I mentioned before:

At \(3 \nmid t\), \(\mathbb{L}_t^*(-)\) is a Landweber-exact theory (that is, the 3-power coefficients of the 3-series of \(E_t\) is a regular sequence in \(Z[[t]]\)).

At \(3 \mid t\), \(\mathbb{L}t^*\) is not Landweber-exact, but is constructible via EKMM by directly killing elements in \(MU\). (This is very similar to the construction for Morava K-theory localized at the prime 3, \(K(2){(3)}\))

Let’s prove this.

| Indeed, that it is not Landweber-exact suggests that Lubin K-theory, at \(3 | t\), behaves like Morava K-theory of height 2; and in general, that Lubin K-theory behaves like a variant of a Morava E-theory of height 2 at the prime 3 (it is in fact Bousfield equivalent). |

Note on a closely related family: The family independently constructed by Behrens, \(y^2 = 4x^3 + u_1x^2 - 2x\) as a universal deformation of the curve \(y^2 = x^3 - x\), the deformation \(y^2 = x^3 + tx^2 - x\) is probably also a universal deformation, which would make \(\mathbb{L}_t\) a model for Morava \(E_2\) at the prime \(3\).

We’ve shown that \(\mathbb{L}^*_t\) is a cohomology theory by directly applying the Landweber exact functor theorem. QED.

Now that we’ve constructed our cohomology theory \(\mathbb{L}_t\), let’s try it out on some routine spaces…

Some computations

Claim: \(E^(B\mathbb{Z}/p) = E^(\mathbb{C}P^\infty)/[p]_F(x)\) for any complex orientable cohomology theory \(E\), with associated formal group \(F\), where \([p]_F(x)\) denotes the p-series of its associated formal group law \(F\).

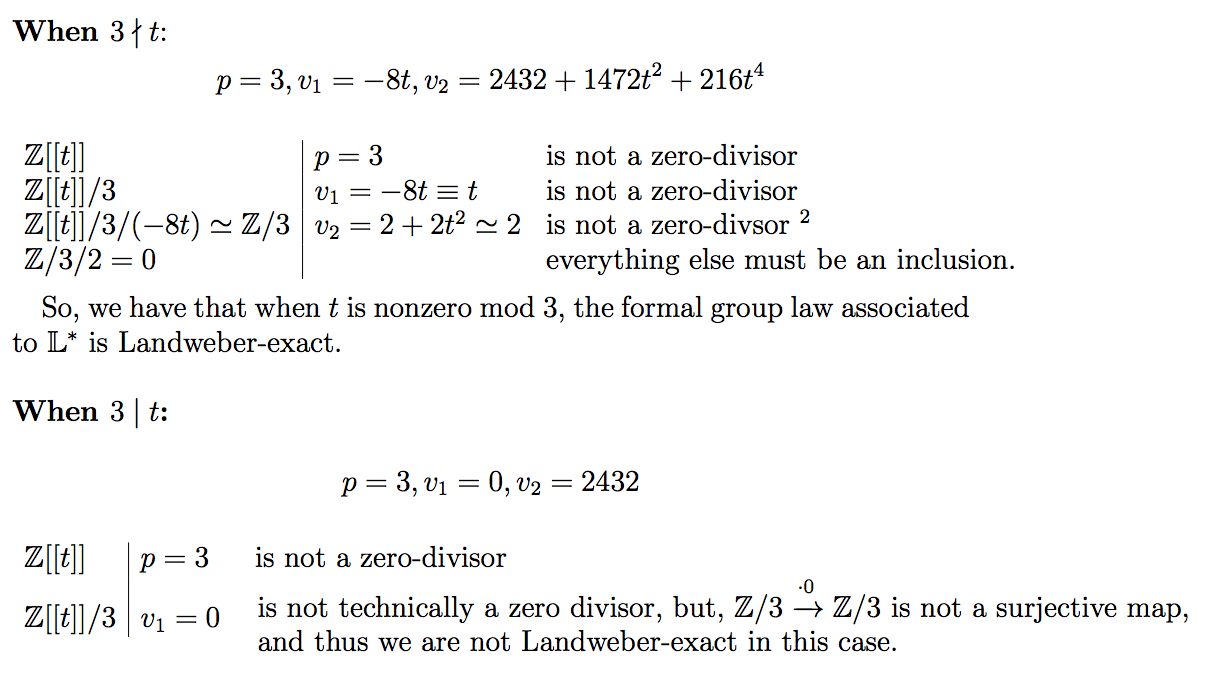

- There is an exact sequence of groups \(Z \xrightarrow{p} \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}/p\)

- Applying “H” gives a cofiber sequence of spectra \(H\mathbb{Z} \xrightarrow{p} H\mathbb{Z} \xrightarrow H\mathbb{Z}/p\). It extends to the right to give the iterated cofiber sequence \(H\mathbb{Z} \xrightarrow{p} H\mathbb{Z} \to H\mathbb{Z}/p \to \Sigma H\mathbb{Z} \xrightarrow{p} \Sigma H\mathbb{Z} \to \Sigma H\mathbb{Z}/p \to \Sigma^2 H\mathbb{Z} \xrightarrow{p} \Sigma^2 H\mathbb{Z} \to …\)

- For spectra, cofiber sequences are the same as fiber sequences, so the above is also an iterated fiber sequence.

- Taking \(\Omega^\infty\) preserves fiber sequences, so the last few nodes give a fiber sequence \(K(Z, 1) \to K(Z/p, 1) \to K(Z, 2) \xrightarrow{p} K(Z, 2)\) of spaces.

- The data of this iterated fiber sequence is equal to the data of the pullback square of fiber sequences

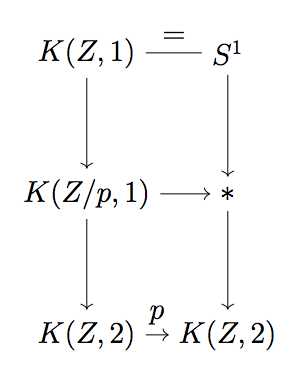

Note that, \(K(Z, 1) = S^1, K(Z/2, 1) = RP^\infty,\) and \(K(Z, 2) = CP^\infty\). As an example, in the case where \(p = 2\): \(E^(\mathbb{R} P^\infty) = E^(\mathbb{C} P^\infty)/[2]_F(X)\):

Returning to the general case, using the AHSS, \(E^{p,q}2 = H^p{cell} (\mathbb{C} P^\infty; E_qS^1) \Rightarrow E^{p+q}(RP^\infty)\)

Theorem (Gysin): For spherical fibrations, there is one differential, multiplication by the euler class (\(d_2(e) = e(\mathcal{L}\))).

From this, we know that \(e(p^\mathcal{L}) = p^(e(\mathcal{L})) = p^*(x) = [p]_F(x)\).

Examples: \(\mathbb{K}^(B\mathbb{Z}/2); \mathbb{L} ^t_(B \mathbb{Z}/2); \mathbb{L}^t_*(B\mathbb{Z}/3)\).

We see that it collapses to \(K^*(RP^\infty) = \mathbb{Z}[\beta^{pm}][[x]]/(2x + x^2)\).

In the case of Lubin K-theory, the 2-series is a unit in \(\mathbb{L}^(CP^\infty)\), so \(\mathbb{L}^(RP^\infty) = 0\) This is reasonable, for the homotopy groups of \(RP^\infty\) are trivial when tensored with \(Z/3\), and \(\mathbb{L}_t\) is inherently \(3\) local due to our family of elliptic curves living over the ring \(\mathbb{F}_3\).

I will state this again to emphasize it’s role: We see that \([p]_F(x)\) is a unit in \(E^(CP^\infty)\) if \(E\) is q-local and \(p \neq q\). Thus, if \(p \neq 2\), \(E^(RP^\infty) = *\).

We see that it collapses to \(\mathbb{L}^*(BZ/3) = \mathbb{Z}[\beta^{pm}][[x]]/[3]_{t}(x)\).

Sidenote: This is all assuming that we have an even periodic family, that is, we started with an ungraded formal group law \(F(x,y)\), and graded it with our periodic element u by multiplicatively conjugating \(u^{-1}F(ux, uy)\) (we are NOT compositionally conjugating by an invertible power series \(u\), which would be \(u^{-1}(F(u(x), u(y))\)). We’ve started in degree 0, and added \(u\) to let us hop up and down degrees. Open question: But what if \(F\), our formal group law, is already graded? I’m not sure!

I can not help but wonder if this method generalizes to the creation of other (besides, say, \(x + y + txy\)). cohomology theories which exhibit “height contraction” behaviour. The next hope is for a construction of height 3 which contracts to height 2. (This remains a hope because I am having difficulty writing down a simple example of a K3-variety which has a one-parameter contraction to a supersingular elliptic curve.)

Sidenote: we use “deformation” in the general setting of viewing any deformation as the replacement of a point \(\text{Spec }k\) with a fat point \(\text{Spf }k[[t]]\).

In summary, at risk of using “pyrotechnical” language:

Morava deforms K-theory by deforming the underlying formal group law, \(\mathbb{G}m\), to the height 1 elliptic curve group \(\mathbb{G}_m/q^\mathbb{Z}\); in modern terms, he constructs tmf in a neighborhood of the cuspidal point of \(M{\ell}^+\) (over \(\mathbb{Z}\)). This is now called “Tate K-theory.”

We constructed a cohomology theory over a neighborhood of a supersingular point \(C\) of \(M_{\ell}\) by deforming the underlying height 2 elliptic curve group, \(C\), into a height 1 elliptic curve group. We call this “Lubin K-theory,” it’s not all Landweber exact, so we didn’t use the same proof method as Morava’s beautiful equivariant sheaf argument.

Some Absurd Speculations: “Chromatic” Coppersmith theory

Don Coppersmith, a student of Sternberg, constructed an answer to the question:

What is a theory of the behavior of homogeneous symplectic manifolds as their parent Lie groups undergo contraction?

This question alone is a beautiful perspective, and suggests a slight adjustment of the traditional approach to chromatic homotopy theory.

What is a theory of the behavior of complex-orientable cohomology theories as their parent smooth algebraic groups undergo contraction?

I’m particularly curious how to relate this theorem by (Chu):

To every simply connected Lie group \(G\) with Lie algebra \(\mathfrak{g}\), every left-invariant closed 2-form induces a symplectic homogenous space.

There is a bijective correspondence between the orbit spaces of 2-cocycles of a given Lie algebra, and equivalence classes of simply-connected symplectic homogenous spaces of the Lie group.

To this quote of Morava (and maybe also to the symmetric 2-cocycles of Lazard):

“Height is a complete invariant for (one-dimensional) formal groups over a separably closed field; in other words, in characteristic p the set of geometric points of \(\Lambda\) stratifies into orbits indexed by the set \(\mathbb{N} \cup \infty\). The orbit of a grouplaw \(F\) is a homogeneous space \(\Gamma/S_F\) and an equivariant sheaf of modules over such a quotient is locally free; indeed, it can be recovered from the action of the isotropy group \(\Gamma/S_F\) of the orbit on the fiber of the sheaf above the point \(F\).”

Why bother to translate Coppersmith theory into the language of formal group laws?

The deformation theory of Lie algebras seems to be pretty hands-on and well developed, and I am a bit desperate for geometric intuition/computational help in thinking about height 2 and height 3 cohomology theories. For example: it would be pretty cool if we could literally deform the model of topological K-theory in complex line bundles to something like bundles with a Poisson-Lie group structure on them (giving us an associative bracket thing a la Poisson geometry). This probably doesn’t make sense, but something like it might!

It’s open how much of Coppersmith’s theory generalizes to our case. In other words, I’m working on it and don’t understand the machinery yet — however, there is hope that the machinery can be translated because both settings can be rephrased as theorems about Hopf Algebras [probably]. [A section in Coppersmith’s thesis that seems to relate directly to our story is \(t-p\)-contractions, or “even-odd”-contractions) which tell us something about the existence of stable isotopy subalgebras.]

Thanks to Dr. Lubin for graciously helping me derive and understand one-parameter families of formal group laws, thanks to Eric Peterson for introducing me to Morava’s Forms of K-theory, thanks to Agnes Beaudry for pointing out that there was a neater way to check for Landweber-exactness.