Dirichlet Series and Homology Theories

Euler was a swashbuckler. He considered the following series, nevermind that it sums to infinity, let’s see what we can do with it!

I highly recommend that you follow along with a pen and paper to convince yourself that everything cancels as I say it will, if you’re a bit too lazy for that, or already familiar with the L-function, feel free to scroll ahead.

\(x = \frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} + … \)

Let’s multiply by 1/2 and see what happens:

\(\frac{1}{2}x = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{10} + …\)

Then subtract this from the original for funsies.

\(x -\frac{1}{2}x\)

\(=\frac{1}{1}\) + 1/2 \( + \frac{1}{3}\) + 1/4 \(+ \frac{1}{5} + …\)

\(= \frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{9} + … \)

\(= (1-\frac{1}{2})x\)

Huh, we’ve taken out all of the multiples of 2.

Hmm, what happens if we multiply the these by 3?

\(\frac{1}{3}(1-\frac{1}{2})x = \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{9} + \frac{1}{15} + \frac{1}{21} + \frac{1}{27} + …\)

Then subtract:

\((1-\frac{1}{2})x - \frac{1}{3}(1-\frac{1}{2})x\)

\(= \frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{11} + \frac{1}{13} + \frac{1}{17} + \frac{1}{19} + \frac{1}{23} + … \)

Notice that \((1-\frac{1}{2})x - \frac{1}{3}(1-\frac{1}{2})x = (1-\frac{1}{2})(1-\frac{1}{3})\)

That’s interesting, we’ve gotten rid of all of the multiples of 2 and all of the multiples of 3.

Let’s take out the multiples of \(5\) that remain, that is, \(-\frac{1}{5}((1-\frac{1}{2})-\frac{1}{3}(1-\frac{1}{2}))x\):

\((1-\frac{1}{2})x - \frac{1}{3}(1-\frac{1}{2})x - \frac{1}{5}((1-\frac{1}{2})-\frac{1}{3}(1-\frac{1}{2}))x\)

\(= \frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{11} + \frac{1}{13} + \frac{1}{17} + \frac{1}{19} + \frac{1}{23} + …\)

Note that we can rewrite this mess: \((1-1/2)x - 1/3(1-1/2)x - 1/5((1-1/2)-1/3(1-1/2))x\) in the aesthetically preferable way: \((1-1/2)(1-1/3)(1-1/5)x\).

And if we keep going, canceling all of the multiples of 7 remaining, then the multiples of 11 remaining, then the multiples of 13 remaining, then the multiples of 17 remaining, …

\(= \frac{1}{1}\) +1/7 + 1/11 + 1/13 + 1/17 + 1/19 \(+ \frac{1}{23} + …\)

What do we have left?

…1/23

Haha, just kidding, when we keep going we cancel everything but the 1 at the beginning:

\([(1-\frac{1}{2}) (1-\frac{1}{3}) (1-\frac{1}{5}) (1-\frac{1}{7}) …]x\) \(= \frac{1}{1}\) +1/7 + 1/11 + 1/13 + 1/17 + 1/19 + 1/23 + …

We only have to make a minor modification to have all of our shenanigans be above board, take the \(s\)th power of each denominator:

\([(1-\frac{1}{2^s}) (1-\frac{1}{3^s}) (1-\frac{1}{5^s}) (1-\frac{1}{7^s}) …]x = 1\)

\(x = \frac{1}{[(1-\frac{1}{2^s}) (1-\frac{1}{3^s}) (1-\frac{1}{5^s}) (1-\frac{1}{7^s}) …]}\)

\(x = \frac{1}{1^s} + \frac{1}{2^s} + \frac{1}{3^s} + \frac{1}{4^s} + \frac{1}{5^s} + … = \Pi_p\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{p^s}}\)

This little guy has a name, his name is the zeta function:

\(\frac{1}{1^s} + \frac{1}{2^s} + \frac{1}{3^s} + \frac{1}{4^s} + \frac{1}{5^s} + … =: \zeta(s) = \Pi_p\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{p^s}}\)

Terminology note: each step, \(\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{p^s}}\), is called an Euler factor (one for each prime), and the whole formula is called the Euler product.

The natural thing to ask is, well, why constrain ourselves to 1 in the numerator? Why not have a function:

\(\frac{\chi(1)}{1^s} + \frac{\chi(2)}{2^s} + \frac{\chi(3)}{3^s} + \frac{\chi(4)}{4^s} + … =: L(s)\)

For example, if I want my \(x\) to look like this:

\(x = \frac{1}{1} - \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} - \frac{1}{7} + …\)

Then I need \(\chi(s)\) that spits out \(\chi(1) = 1\), \(\chi(2) = 0\), \(\chi(3) = -1\), etc.

This L(s) is called the L-function or Dirichlet series, and it is of great interest to people in general, particularly in the study of rational points on curves.

But, if you’ve been reading this blog for very long, you won’t be suprised to hear that I am interested because they come up in the dialogue between formal group laws and complex homology theories.

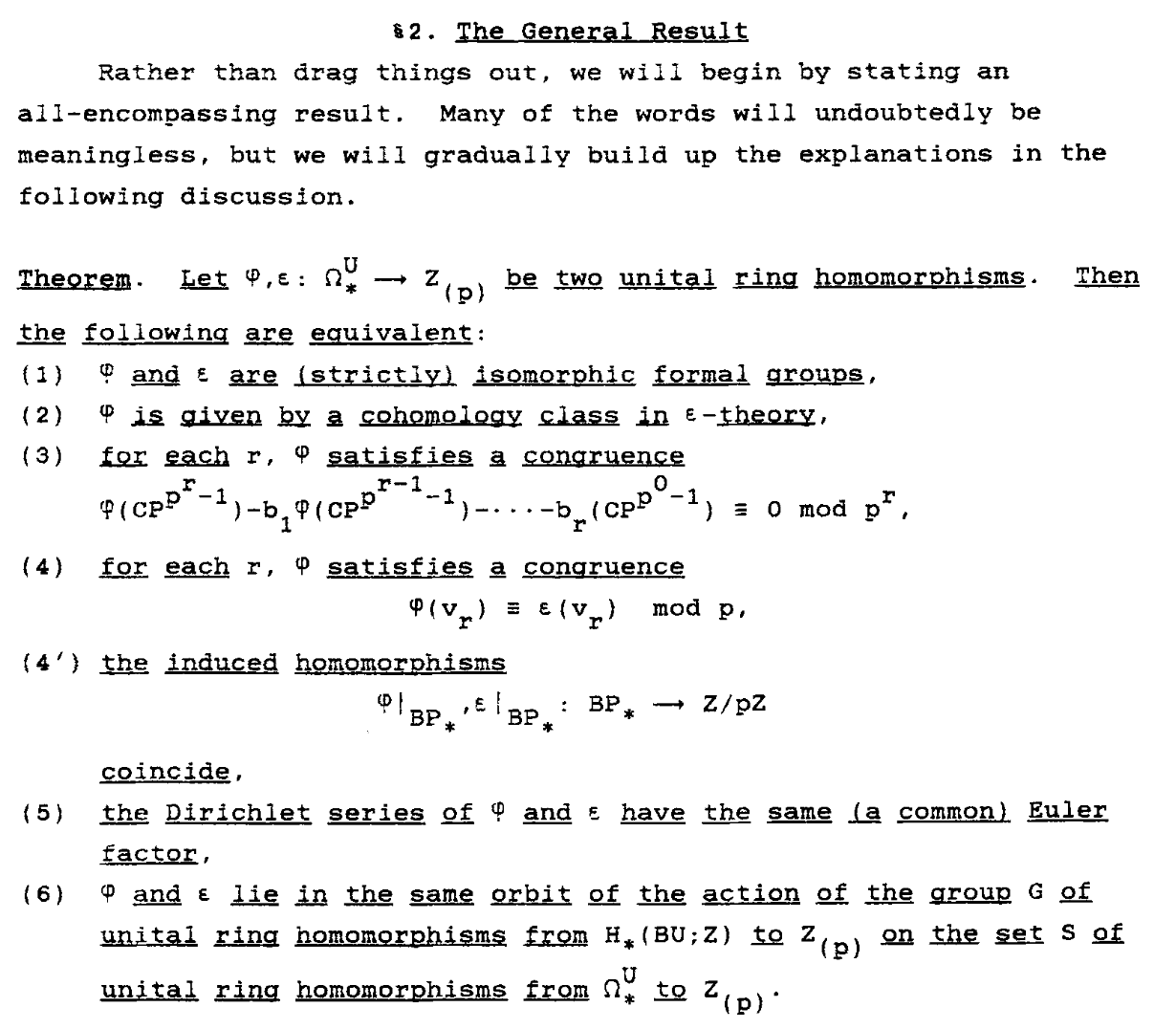

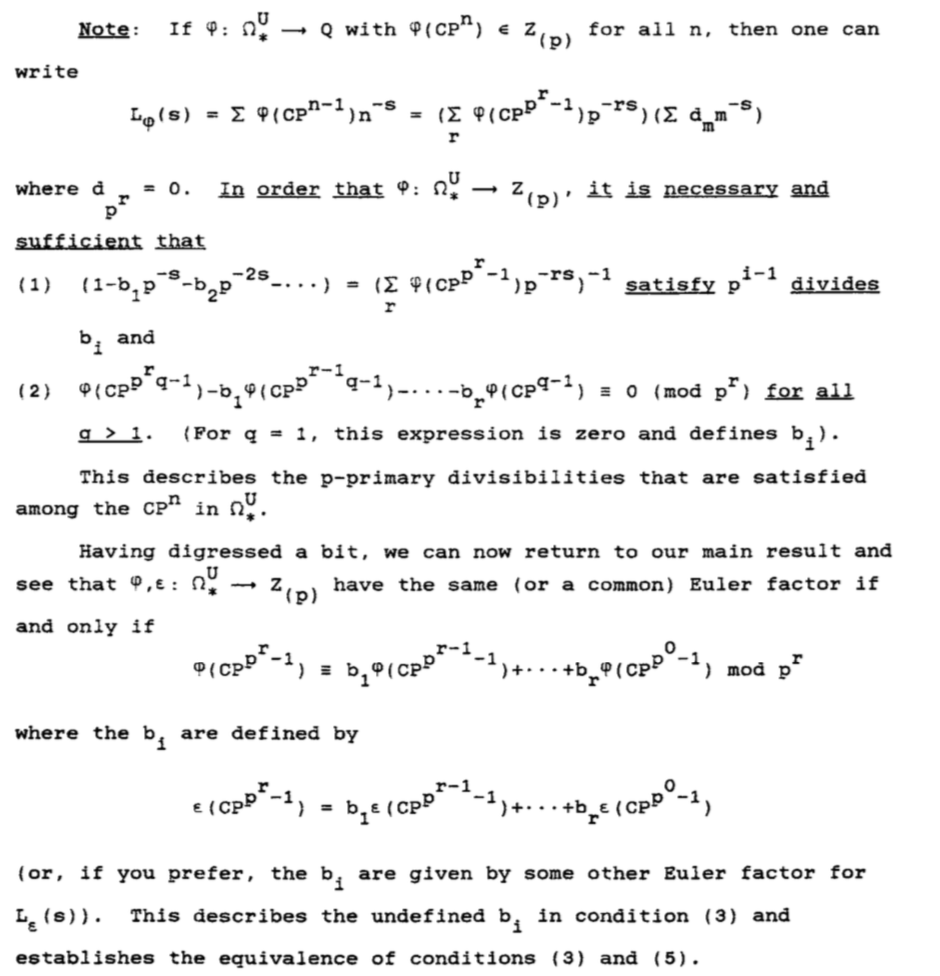

Specifically, I’ve been wondering about (5) in this excerpt of the paper “Dirchlet Series and Homology theory” by Smith and Stong:

Note that it is not ridiculous for (3) to be equivalent to (5): the \(b_i\) are defined in terms of \(L_{\epsilon}\), so secretly \(\epsilon\) is present in the statement of (3).

We’ve been acquainted with the notion of a Dirichlet series and an Euler factor. At last, we can decipher the meaning of (5).

Recall that a genus is an operator that takes in a manifold (up to some equivalence relation) and spits out a number that characterizes it — of great interest to any who care about algebraic invariants. More specifically, an “\(R\)-genus” is a ring homomorphism \(MU_* \xrightarrow{g} R\) from (complex-oriented) cobordism classes of manifolds to a commutative ring \(R\).

Keep in mind that in the rational case, the generators of the ring \(MU_\) are the complex projective spaces of each dimension, \(P^n\). \( MU _ \otimes Q \simeq Z[P^n]\)

Given a genus \(g\), we can build a few different things to study its properties in a more manageable form. Today, we’re just going to mention two associated formal power series: the Dirichlet series, and the series we get out of Hirzebruch’s construction.

- \(L_g(s) := \sum_{n \geq 1} \frac{g(P^{n-1})}{n^s}\)

- \(\hat{g}(z) := \sum_{n \geq 0} g(P^n)z^n\)

For example, let’s say \(g(P^n) = 1\) for all \(n\), (that is, \(g\) is the Todd genus) then \(L_g(x) = \sum_{n \geq 1} \frac{1}{n^s}\). The classical fella, \(\zeta(s)\), that we started this post with!

This isn’t just interesting, it also gives us a pretty useful theorem, which tells us that the p-primary divisiblility which takes place in \( MU_* \) can be nicely described in terms of the L series associated to objects in \(Hom_{Ring}(MU_*, -)\).

Keep in mind that Quillen proved that \(MU_* \) is the universal formal group, so, for example, a ring homomorphism from \(g: MU_* \to Z_{(p)}\) is nothing more than a formal group structure for \(Z_{(p)}\).

This was a world-shaking result. It began to give us hope looking at the seemingly orderless, complicated, multi-layered signal sent by the stable homotopy groups of spheres. Quillen’s result led to first localizing this “signal” at a prime, then engineering various band-pass filters to isolate the individual messages, i.e., breaking this complicated multi-layered object into layers.

In this breathtaking paper, Morava eloquently states: Screen Shot 2015-07-06 at 10.37.37 PM.

To my dismay, I still don’t understand Quillen’s proof. But let’s get back to the Dirichlet story.

I’ll mention one more interesting thing about \(L\)-functions in this story.

As a subset of \(Hom_{Ring}(MU_*,Q)\), let’s look at the set of maps that send \(Z[P^n] \to Z_{(p)}\).

- This set is in bijective correspondence with the set of { \(L\)-series with \(Z_{(p)}\) coefficients, having leading term 1 }.

- This set is endowed with an abelian group structure via the multiplication of \(L\)-series (series beginning with 1 are invertible).

- Inside this group, we have a subgroup, \(G\), given by the group of series:\(\sum \frac{g(P^n)}{n^s}\) for which \(g(P^{p^r1-1}) \equiv 0 \mod p^r\).

- So the two series \(L_g\) and \(L_f\) with \(g, f\) have the same Euler factor iff they lie in the same orbit of \(G\).

Thanks to Laurens Gunnarsen for explaining the L-function, and to Peter Teichner for letting me borrow his copy of Landweber’s book “Elliptic curves and Modular forms in algebraic topology.”