Spin Manifolds

Disclaimer: This exposition is profane. It is the result of me trying to be productive during a raging headache, and ending up with comic relief.

I recommend this to be read when you are looking for a laugh, or already feeling silly.

The motivation for the field of differential geometry can be thought of as a large group of punk math students screaming:

“We won’t wait for the world to let us study change! We want to differentiate on whatever we want! Give us more interesting manifolds than just \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Fuck the Euclidean system!”

A rough and ready definition of an \(n\)-dimensional manifold is a topological space which looks locally like what the government wants \(\mathbb{R}^n\). With this in mind, my punk math friends, let’s figure out how to study change.

First, how the hell do we assemble the tangent spaces at various points of a manifold into a coherent whole?

I hope we can agree that the total derivative of a \(C^{\infty}\) function should change in a \(C^{\infty}\) manner from point to point.

We create this differentiability for functions over our manifold M by considering behavior in the overlaps of coordinate neighborhoods.

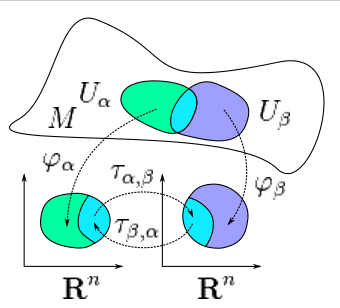

Consider an arbitrary point \(p \in M\), and two distinct neighborhoods \(U_\alpha\) and \(U_\beta\) which both contain \(p\).

The transition map \(\tau_{\alpha, \beta}:= \psi_\alpha^{-1}\psi_\beta\) (fuck you I’ll put composition in any order I want, it’s a free country)

is the type \(\tau_{\alpha, \beta}: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^n\). This map better be \(C^\infty\) (differentiable arbitrarily often), or you’re going to have a bad time doing calculus on that motherfucker.

There are many sorts of manifolds, with different requirements for continuity of these transition maps.

In our case, we want to do calculus without a hitch, so we’ll insist that all of our transition functions must be \(C^\infty\), and refer to such manifolds as “smooth”.

We’re working in a category, where our

- objects = smooth manifolds

- morphisms = \(C^\infty\)-maps between these smooth motherfuckers

We call this category “Diff”, which is the category-cool version of saying “let’s do some differential topology up in this bitch.”

When you hear “Let’s do calculus” your “We’re working in Diff!” alarm bells should go off.

Alright, I’m getting off track. How do break out of the cage imposed by the Euclidean system? Let’s start with some tangent bundles.

That’s right kids, it’s a fucking fiber bundle!

Our manifold \(M\) is the base space, and the fiber (over each point \(p\) in \(M\)) is just the tangent plane over that point, which we’ll denote as \(T_p(M)\) because I’m lazy and don’t want to type “the tangent plane over the point \(p\) in our manifold \(M\)” each goddamn time.

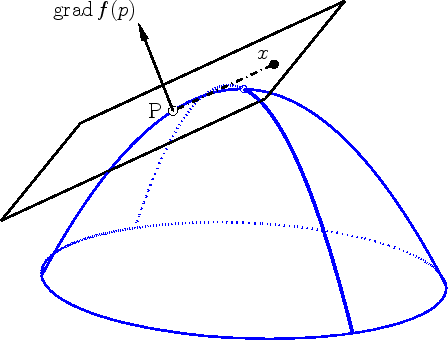

If you’re visual thinker like me, here are some pictures to make you feel good about yourself.

Oooh, ahhhh. So shiny.

Alright, I’m going to keep being lazy and give some more shorthand names, claiming that it’s for clarity:

Let \(V^n\) := the set of all column vectors of height \(n\) and \(U\) := an open subset in \(\mathbb{R}^n\)

Recall that we’re working with a fiber bundle, the tangent bundle \(T(M) = U \times V^n\)

The base space is our manifold \(M\) the fibers are our tangent plane \(T_p(M) = p \times V^n\)

Of course, this tells you jack shit about how to actually compute the tangent plane given any point on a surface, but you can go look in any standard multivariable calc book for that stuff.

Motherfucking Modules

Think the tangent bundle is general as fuck? You obviously haven’t read enough Grothendieck. The tangent bundle is an example of a motherfucking module bundle.

A module bundle exactly what you think it is: a bundle with fibers that are motherfucking modules.

These are usually called vector bundles, but my ring-theorist-friend convinced me that I have to use modules all the time to get an intuition for them, so I’m trying that. In his words: who needs inverses anyway when we can formally append them. I’m not used to modules yet, so I’ll probably commit the sin of switching between modules and vector spaces as we go.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, talking about module bundles before defining a module. Let’s back the fuck up.

What is a motherfucking module?

a vector space - requiring property of invertibility = a module

If you’re feeling like a tight-ass today, here’s the rigorous-as-fuck (RAF) definition of a module in stuff, structure, properties form (aka Baez-style).

Let \(R\) be a ring and \(1_R\) be its multiplicative identity.

(stuff): A left \(R\)-module \(V\) consists of an abelian group \((V, +)\)

(structure): and an operation \(R \times V \to V\) ; aka we’re closed under this bitch.

(properties): such that \(\forall r,s \in R\) and \(x, y \in V\)

distributive as fuck:

- \(r(x+y) = rx + ry\)

- \((r + s)x = rx + sx\)

associative as fuck:

- \((rs)x = r(sx)\)

and of course, the multiplicative identity holds, because rings are not pathological little fucks (okay, fine maybe the ring of integers of \(\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt{-5})\) are little fucks but they still obey this property)

- \(1_Rx = x\)

BUNDLES of Motherfucking Modules

We can look at these module bundles in at least 2 ways. More if you get creative, but you heard what happened in Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared.

-

We have a module space assigned to each point in a manifold in such a way that as we move smoothly over the manifold, the module twists smoothly.

-

Locally a module bundle is trivial, so what we care about are the transition functions. These must lie in the automorphism group of our module.

What properties do we need to slap on these motherfuckers to make them play nice with spin representations?

Our manifold \(M\) must satisfy:

- orientable

- Riemmanian

- 2nd Stiefel-Whitney class vanishes

If all of these conditions hold, we say \(M\) is spin, because who the fuck wants to write “manifold that is orientable, Riemannian, and whose 2nd Stiefel-Whitney class vanishes” every time they talk about slapping a spin structure on a manifold.

Go forward unabashed, even if you don’t know what these words mean. I’m about to tell you!

ORIENTABLE

We want our bundle to be orientable, which we can define as a continuation of our previous module bundle definitions:

-

If we can choose a frame which varies smoothly over the manifold (and is always a frame), our bundle is orientable.

-

If our transition functions all lie in the special orthogonal group, SO(n), our bundle is orientable.

DO YOU EVEN LIFT, SO(n)?

We need our manifold’s structure group, SO(n), to lift to spin. If it lifts to spin, we can describe the Dirac operator globally!

confetti

But you shouldn’t fucking believe everything I say — I hope you’re asking yourself “what the fuck does that even mean?”

What the fuck is a spin GROUP?

Praise the Flyng Spaghetti Monster, the concept of a Spin group is hella geometric.

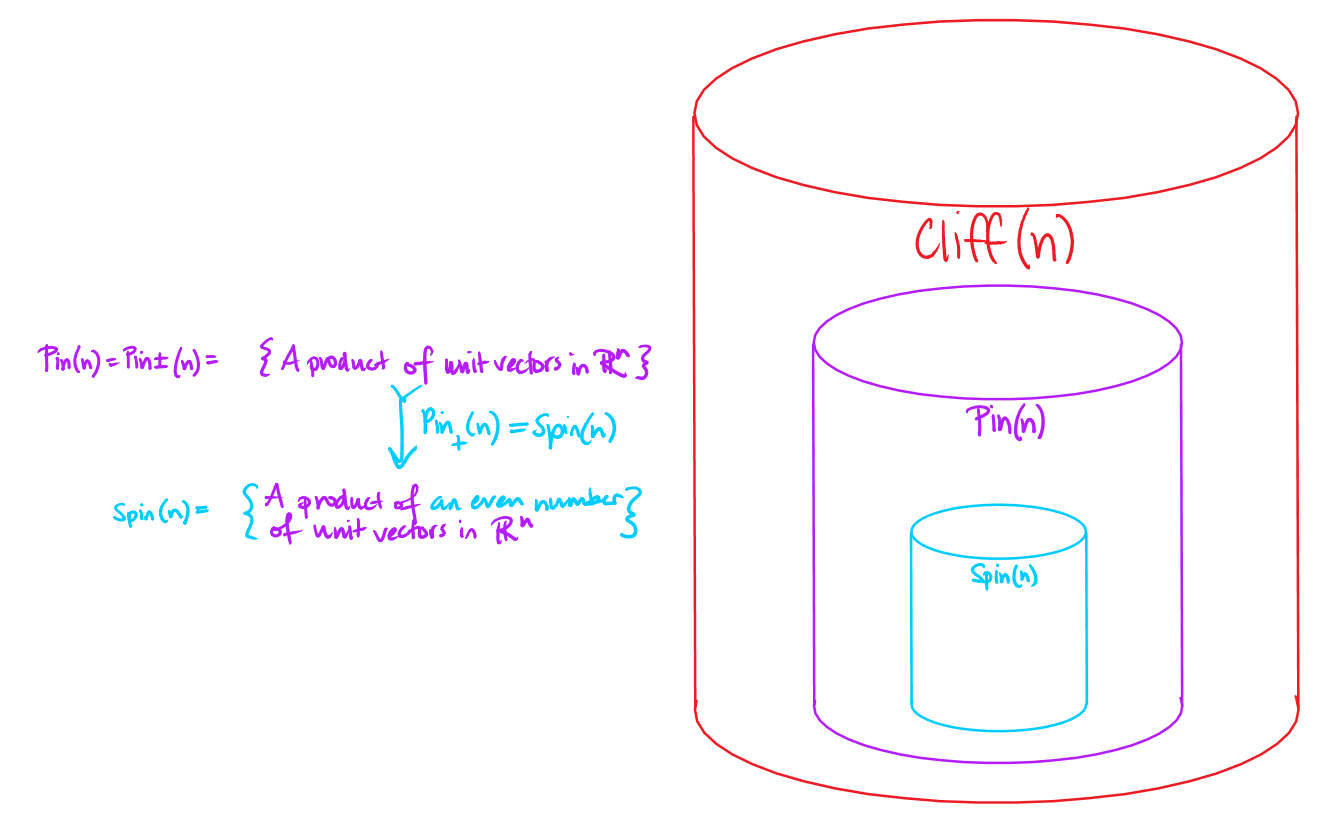

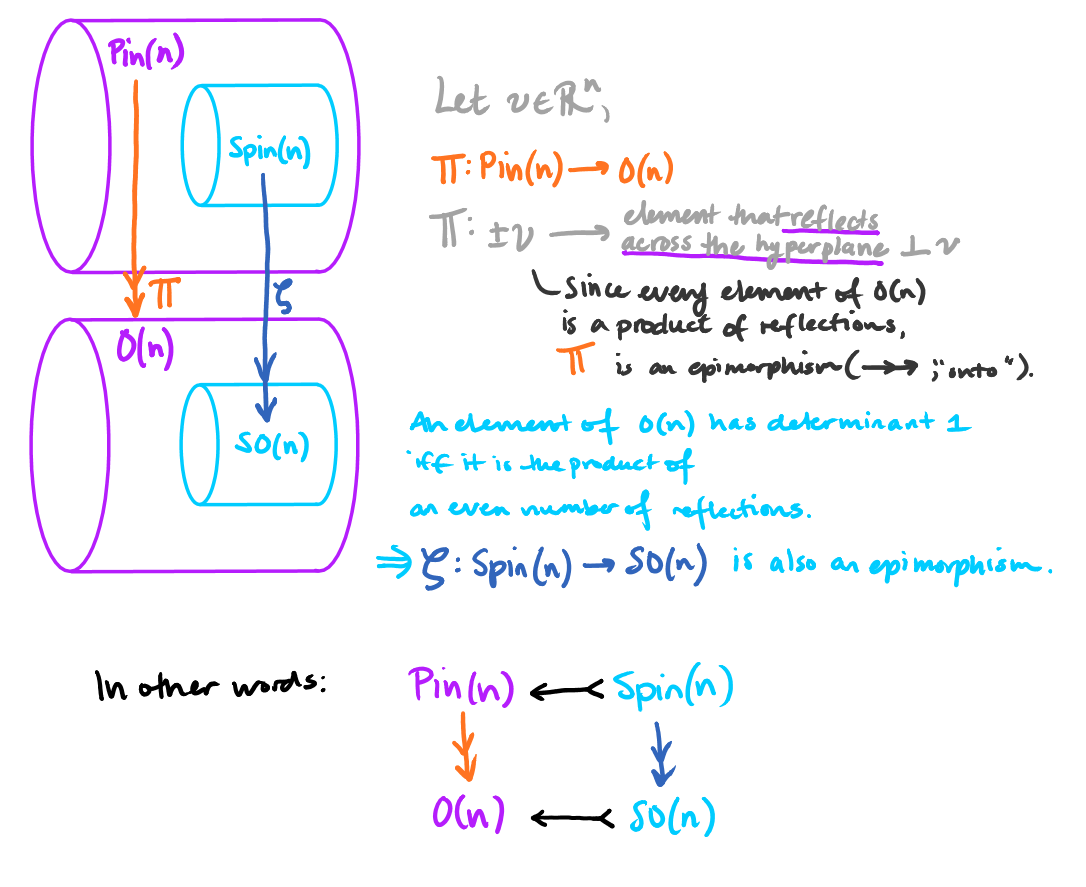

Below are illustrations of the \(n\)-dimensional Spin group, \(\text{Spin}(n)\), as a subobject of their corresponding \(C\ell\) algebra:

What the fuck is a spin STRUCTURE?

The structure group of any principal \(G\)-bundle \(E \to B\) is just \(G\).

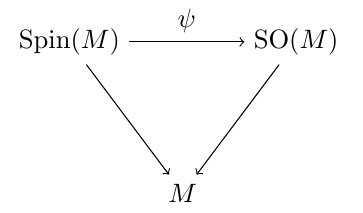

It should come as no surprise that a spin structure on our manifold \(M\) is composed of

- a principal \(Spin(M)\)-bundle, \(\text{Spin}(M) \to M\)

- a bundle morphism \(\psi\) from \(\text{Spin}(M) \to M\) to \(SO(M) \to M\)

which restricts fiberwise to the covering homomorphism \(\text{Spin}(M) \to \text{SO}(M)\).

RIEMANNIAN

We study the notion of curvature and its relation to topology under the name ‘Riemannian geometry’, which is where most of the ‘geometry’ in ‘differential geometry’ comes out to play.

Don’t forget that we’re in \(\text{Diff}\)! Our manifolds are smooth motherfuckers.

Slap a Riemannian metric on that motherfucker and we get smoothly varying choices of inner product on tangent spaces.

Fuck yes! Let’s introduce a Riemannian metric on the manifold. In other words, let us pass from \(GL_n\) to the maximal compact subgroup \(O_n\).

orientation = reducing the structure group from \(O_n\) to \(SO_n\) spin structure = then lifting the structure group to the universal covering group \(Spin_n \to SO_n\).

When does the structure group lift to Spin?

Recall that transition functions must satisfy the cocycle condition.

Thus, lifts of the transition functions must also satisfy this condition. When this is possible, we can attach a spin bundle by specifying that its transition functions = the lifts of the transition functions of the cotangent bundle.

Henceforth, I’ll assume that you motherfuckers are cool with homology and homotopy. I’m also hella tired right now, so the rest of this is a bit wibbly.

All I’m tryna say is: the structure group lifts Spin to if there is no obstruction.

There is no obstruction if the 1st and 2nd Stiefel-Whitney classes vanish (i.e. \(w_1 = w_2 = 0\)).

Don’t take my word for it! You should be asking: what the hell are these classes and what do they have to do with structure groups?

The conditions \(w_1\) and \(w_2\) can be interpreted geometrically as follows.

Let \(E\) be a vector bundle over a manifold \(M\). Then \(E\) is orientable iff the restriction of \(E\) to any circle embedded in \(M\) is trivial.

If \(M\) is simply-connected and \(\text{dim}(M) < 4\), then \(E\) is spin iff the restriction of \(E\) to any 2-sphere embedded in \(M\) is trivial.

Why? \(H_2(M, Z/2)\) is generated by embedded 2-spheres (when \(\pi_1 = 0\) and \(\text{dim}(M) > 4\)).

Let \(O_n\) be the orthogonal group. Before I go, I want to tell you something enticing.

- \(\pi_1(O_n) = \mathbb{Z}/2\) — orientations and \(w_1\) (1-connected cover)

- \(\pi_2(O_n) = \mathbb{Z}/2\) — spin structure and \(w_2\) (3-connected cover)

- \(\pi_3(O_n) = 0\)

- \(\pi_4(O_n) = \mathbb{Z}\) — string structure and \(p_1/2\)

- …

Let’s say that \(X\) and \(Y\) are some smooth motherfuckin’ manifolds. When is a map \(X \xrightarrow{f} Y\) null-homotopic?

When that shit LIFTS. \(f\) better induce a zero map between the homotopy groups.

\(H^n(X; G) \simeq [X; K(G,n)]\)

If this isomorphism isn’t up your alley, then I highly suggest you revaluate your life decisions because it is sick as fuck! If you’ve never seen it before, have some John Baez!

\(Y_1 \to B^2(\pi_2(Y_1)) = B^2\pi_2(Y)\)

\(c \in H^2(Y_1, \pi_2(Y))\)

\(Y_n\) lifts to \(Y_{n+1}\) if a cohomology class in \(H_{n+1}(X, \pi_{n+1}(Y))\).